12 Temporal Features

Feature engineering with data that requires predictions into the future from a fixed moment that leverages all the present and past known within the data creates complicated wrangling problems. As we move through our historical data to create training data that respects the division between past, present, and future we face a unique challenge that our features and target value can often be identical measures only differentiated by our defintion of the present or NOW.

Additionally, time series data also introduces complexities with highly correlated observations. When dealing with time series data, we need to account for the temporal dependencies and autocorrelation present in the data. Our feature engineering often requires creating lag features, rolling statistics, and other time-based features to capture the underlying patterns and trends.

Lag features are simply the values of a variable at previous time steps. For example, if we are predicting sales, we might include the sales from the previous day, week, or month as features. Another approach is to calculate rolling statistics, such as the rolling mean or standard deviation, to capture the trends and variability over time.

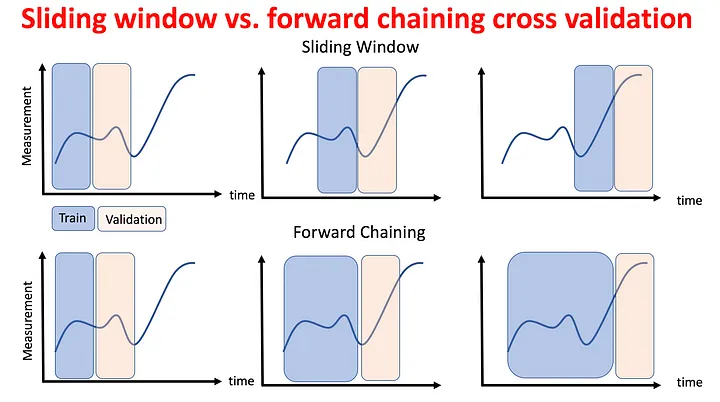

We need to be mindful of the potential for data leakage, where information from the future is used to predict the past. This can lead to overly optimistic performance estimates and poor generalization to new data. To avoid this, we should ensure that our feature engineering and model evaluation processes respect the temporal order of the data.

12.1 Exploring spatial munging

Alakh Sethi has a fun post on Feature engineering that highlights some great thoughts about temporal data and feature engineering.

Peeking (into the future) is the “original sin” of feature engineering. It refers to using information about the future (or information which would not yet be known by us) to engineer a piece of data. This can be obvious, like using next_12_months_returns. However, it’s most often quite subtle, like using the mean or standard deviation across the full-time period to normalize data points (which implicitly leaks future information into our features). The test is whether you would be able to get the exact same value if you were calculating the data point at that point in time rather than today.

Be honest about what you would have known at the time, not just what had happened at the time. For instance, short borrowing data is reported by exchanges with a considerable time lag. You would want to stamp the feature with the date on which you would have known it.

12.2 Example Data

We will use some data about grocery stores in South America. The data includes daily transactions, store metadata, and promotional information. This dataset will help us understand how different factors influence sales and transactions at various stores. It is based on a Kaggle competion1

Let’s take a look at the datasets we have:

transactions_daily.parquet: Contains daily sales data for each store and product family.transactions_store.parquet: Contains the total number of transactions per day for each store.stores.parquet: Contains metadata about each store, including location and type.

We will use these datasets to demonstrate feature engineering techniques for building predictive models.

12.2.1 transactions_daily.parquet

The primary data, comprising time series of features store_nbr, family, and onpromotion as well as the target sales.

store_nbr: identifies the store at which the products are sold.family: identifies the type of product sold.sales: gives the total sales for a product family at a particular store at a given date. Fractional values are possible since products can be sold in fractional units (1.5 kg of cheese, for instance, as opposed to 1 bag of chips).onpromotion: gives the total number of items in a product family that were being promoted at a store at a given date.

12.2.2 transactions_store.parquet

The total transactions by day for each store.

store_nbr: The store number.transactions: The total number of transactions for that day.

12.2.3 stores.parquet

Store metadata, including city, state, type, and cluster.

cluster: is a grouping of similar stores.

12.2.4 Data downloads

12.2.5 Data Munging Challenge

Let’s explore how to build temporal features with a walk through some feature engineering using the grocery store data.

Pourya’s article in Toward’s Data Science provides some simple examples of timeseries feature engineering that we will use with our data.

We can start with our transactions_daily.parquet data.

import polars as pl

from lets_plot import *

LetsPlot.setup_html()

daily = pl.read_parquet("transactions_daily.parquet")Starting with the date column, let’s move our daily transactions to weekly summaries for each store and product family with the following new columns.

week_of_yearyearmin_datein the week of year by year.max_datein the week of year by year.total_salesfor that week.prediction_dayor the day we define as the NOW that devides historical knowledge and future ‘unkowns’.

After we create our weekly data, we can answer the following questions.

- What day do weeks of the year start on?

- What is wrong with the date 2013-12-31?

- What is wrong with the date 2017-01-01?

- Can you fix this issue with weeks and years?

Ok. Now that we have created our proper weekly data,

- Can you create the following table for 2017 SEAFOOD?

| store_nbr | family | week_of_year | year | prediction_day | min_date | max_date | num_days_in_week | 1_week_behind_sales | 1_week_ahead_sales | 2_week_ahead_sales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 45 | 2016 | 2016-11-06 | 2016-11-07 | 2016-11-13 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 19 |

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 46 | 2016 | 2016-11-13 | 2016-11-14 | 2016-11-20 | 7 | 3 | 19 | 5 |

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 47 | 2016 | 2016-11-20 | 2016-11-21 | 2016-11-27 | 7 | 19 | 5 | 8 |

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 48 | 2016 | 2016-11-27 | 2016-11-28 | 2016-12-04 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 10 |

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 49 | 2016 | 2016-12-04 | 2016-12-05 | 2016-12-11 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 50 | 2016 | 2016-12-11 | 2016-12-12 | 2016-12-18 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 6 |

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 51 | 2016 | 2016-12-18 | 2016-12-19 | 2016-12-24 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 5 |

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 52 | 2016 | 2016-12-25 | 2016-12-26 | 2016-12-31 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| 54 | SEAFOOD | 53 | 2016 | 2015-12-31 | 2016-01-01 | 2016-01-03 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 12 |

Notice how time is moving along columns and rows. As we move down rows we are moving into the future. In the columns, we would have one column (in our example we have two potential columns) that is in the future which would be used as the foundation (or the actual) target (y) variable. The remaining time-based columns would be summaries of intervals or points in the history of the point of estimation.

- Which column would be our

yvalue ortargetif we were predicting what we will sell in the next seven days? - How do the three date columns (

prediction_day,min_date,max_date) relate to ourtargetvariable. - Can you build a new

ythat is the lagged difference? The column would be the difference in sales from the week we just completed to the sales seven days in the future. - Can you build a new

featurethat is the difference in percent of sales for the year comparing the most recently completed week with it’s sister week in the previous year? - How correlated is this new

featurewith ourtarget?

- Explore the example Polars script

12.3 Exploring spatial modeling

- Time Series Machine Learning Regression Framework | by Pourya | TDS Archive | Medium

- Cross Validation in Time Series. Cross Validation: | by Soumya Shrivastava | Medium

- How (not) to use Machine Learning for time series forecasting: Avoiding the pitfalls | by Vegard Flovik | Towards Data Science | Medium

- How (not) to use Machine Learning for time series forecasting: The sequel - KDnuggets

- Fine-Grained Time Series Forecasting With Facebook Prophet Updated for Apache Spark - The Databricks Blog

- modeling - Using k-fold cross-validation for time-series model selection - Cross Validated

- Cross-validation for time series – Rob J Hyndman

- 3.4 Evaluating forecast accuracy | Forecasting: Principles and Practice (2nd ed)

- time-series-foundation-models/lag-llama: Lag-Llama: Towards Foundation Models for Probabilistic Time Series Forecasting

Alexis Cook, DanB, inversion, and Ryan Holbrook. Store Sales - Time Series Forecasting. https://kaggle.com/competitions/store-sales-time-series-forecasting, 2021. Kaggle.↩︎